→ ESTATE

Diana Miziri

(1951 – 2005)

Tirana, Albania

THE ESTATE

The estate of Diana Miziri (1951–2005), managed by her husband and their two children, consists of a significant number of textile works mainly produced during the 1990s. They are mostly woven or embroidered, with materials such as wool, linen, cotton, acrylic, and recycled coffee and rice sacks. In the early 90s in Albania, it was difficult to find proper, quality working materials, so it was more feasible for her to reuse materials and adapt them through a home colouring process. All of them are handmade, woven without a loom, in the home environment. She improvised adjustable auxiliary structures where the piece was fixed. For the weaving she used large needles, up to 15 cm long, which she also produced herself. The formats vary from 60 cm to 250 cm in height.

Working without the fixed frame of the loom, her textiles became freer and more experimental. Her basic training was in painting, and that was her starting point. In the beginning she didn’t want to pursue a specialization in textiles, which was “imposed” on her by the system of the time. Textiles ultimately became her favourite medium of expression, but she approached them more from a pictorial awareness.

Before the 1990s, in Albania textiles were mainly integrated into functional design, for creation of rugs, carpets, fabrics and other elements meant for decoration, and textiles were not practised or regarded as an art form per se. Under the Socialist Realist directives, the motifs and patterns used in textiles had to be inspired by traditional elements. Nevertheless, textiles were one of the few media in which geometrical and abstract expressions were accepted and allowed, as compared to painting and sculpture, where any departure from the figurative Socialist Realist dogma was not only unacceptable but was severely punishable with detention and persecution.

Diana’s textile creations from the 90s result from a liberation from functional design and a return to free and experimental pictorial expression. It should also be stressed that in the 20th century, Albanian art developed from classicism to Socialist Realism, skipping modernism and postmodernism, only to be confronted with contemporary art in the 90s. Due to the country’s extreme isolation and its attempt to forbid any foreign and modernist influences, artists were mostly unaware and uninformed about art history from Impressionism onward.

In this context, Diana’s textile works from the 90s should be understood as the solo expression of her own aesthetic understanding, which was purely an intuitive expression, freed from references, influences and dialogue with any association foreign to her own experience.

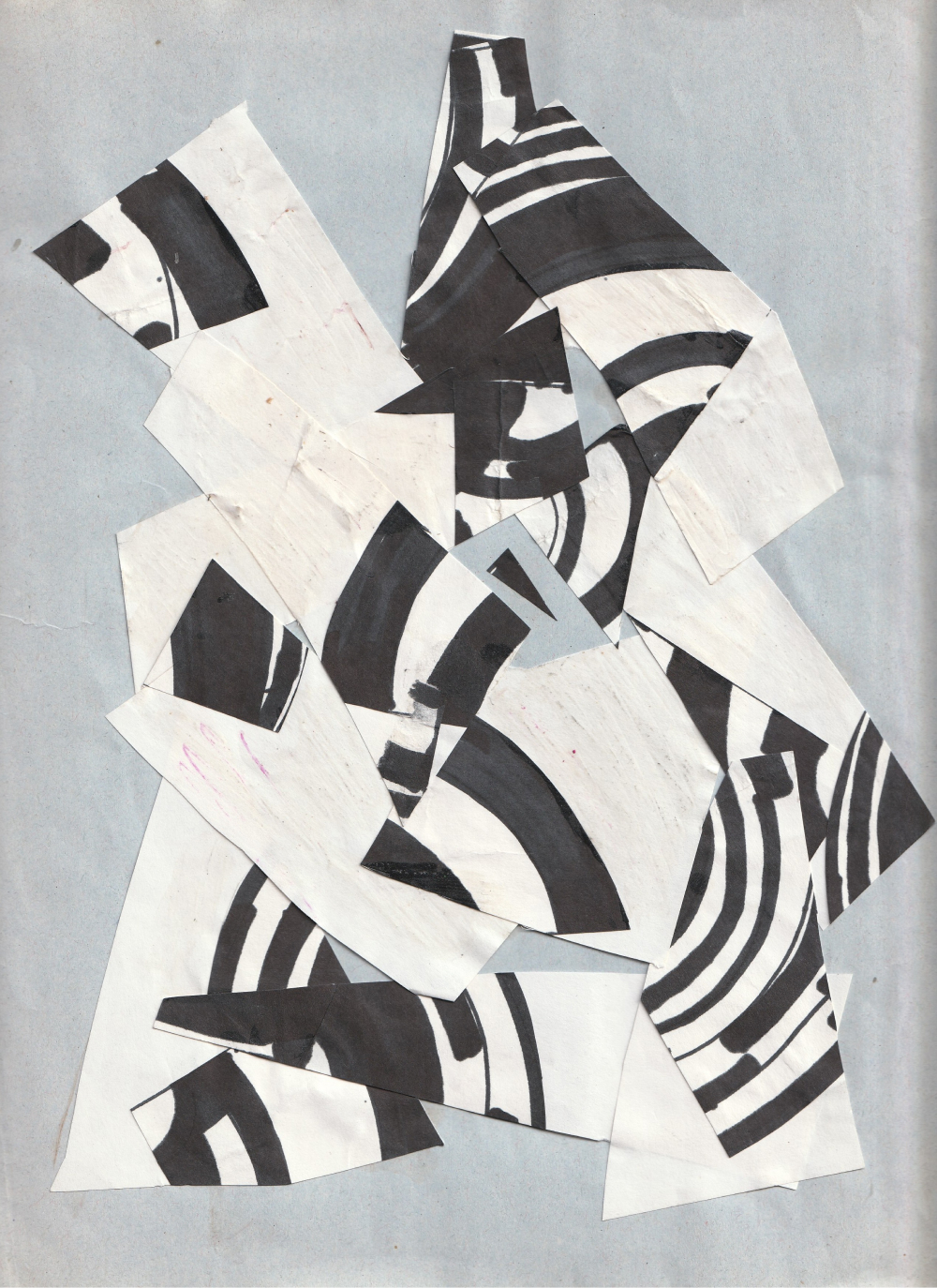

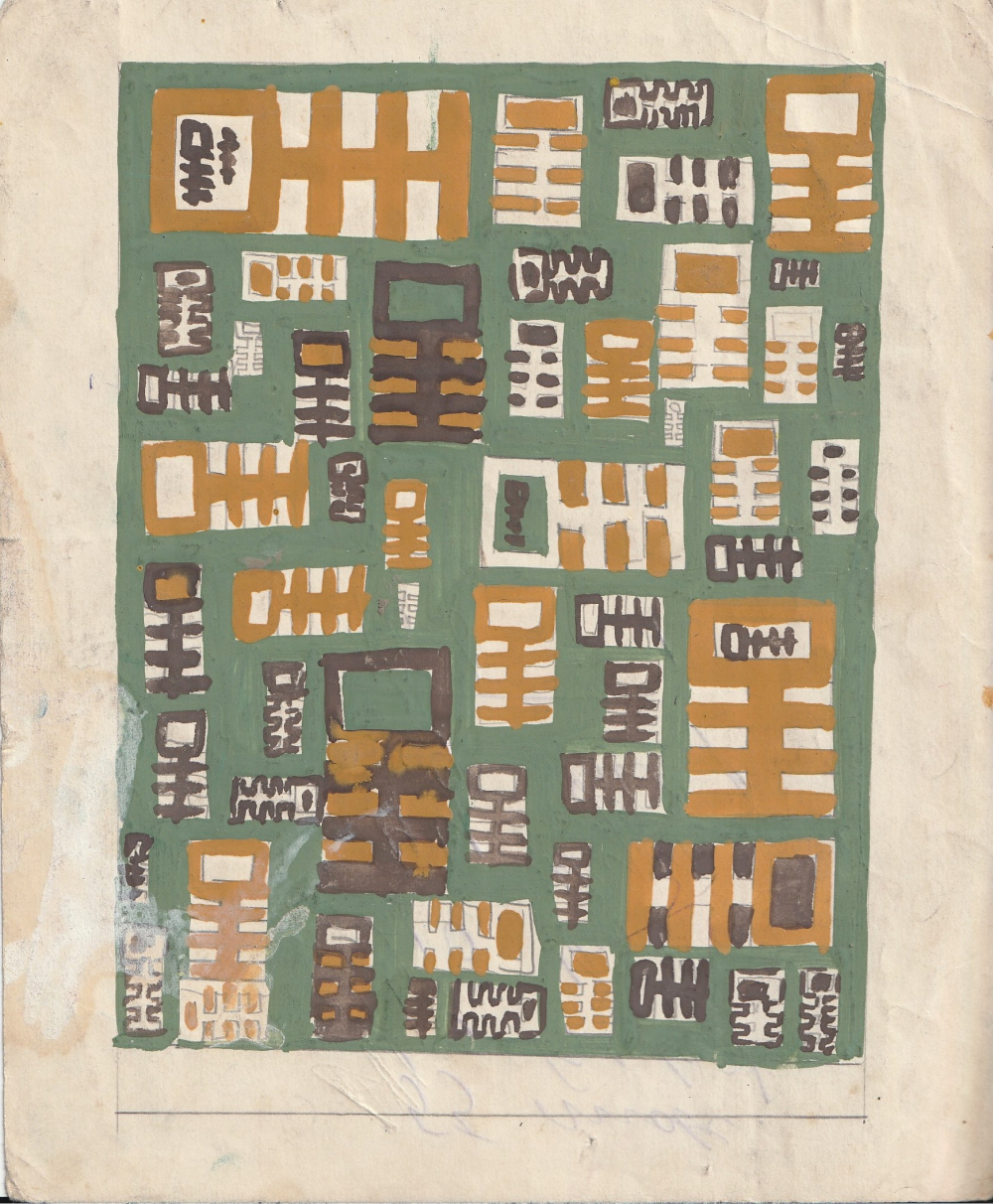

A major part of her estate includes sketches and drawings that served as a starting point for the creation of the textile works. Some of the textiles were ultimately produced, but many of them remain unrealized. The sketches were mainly made using coloured pens and stencils on white paper, in various small formats, from a few centimetres to A4 size. They served more for composition, focusing on creation of shapes and layers, using only two or three colours: blue, black and red. The colours were apparently chosen later, in the execution phase. We could infer that often it was the found materials that dictated the palette used in the final work, but we also know that Diana and her family often dyed the threads manually according to her needs. Some sketches are devoted to installation projects foreseen for larger spaces and made up of many textile pieces.

Part of the estate is clothing and accessories designed and produced by Diana in the early 90s for the first fashion design competitions in Albania. She never really had a proper studio, and often worked at home or in the classroom where she taught. From 1995 she shared a small studio with her husband, where most of her textile works are stored today.

Diana passed away in 2005, following an acute and rapidly progressing illness. Her practice, as well as the stories of many other women artists whose careers started in Albania under communism and transformed in the course of the country’s democratic transition, lacks proper research, visibility and promotion. Curator Adela Demetja, who had the chance to meet Diana at the Jordan Misja Art Lyceum of Tirana, through her daughter Ela, rediscovered the works of Diana in 2020 as part of her research for an exhibition project.

Diana Miziri’s estate is a precious resource for the development of textiles as an art form in Albania, but the works are in need of restoration and could face difficulties in conservation in the upcoming years.

THE ARTIST

Diana Miziri’s desire to pursue art was deeply personal, and her family recognized and supported this passion. From an early age, she participated in art drawing courses in her hometown of Durrës. Later, she pursued higher education at the forerunner of the Tirana University of Arts, specializing in textile design. Although textile design was not her first choice, she embraced it wholeheartedly. This field ultimately became the primary medium of her artistic practice.

Diana was a member of the generation of Albanian artists studying during a period when the Tirana art academy was undergoing a transformation, broadening the program to include specializations like textile design, graphics, ceramics, monumental painting, and so on. During her studies she met her future husband, Fatmir Miziri. In 1973 they both graduated from the painting department, where Diana specialized in textile design and Fatmir in glass design. Diana and Fatmir often collaborated on joint creations and exhibitions. Their two children, Ela and Oert, who studied art and architecture, were involved in their parents’ artmaking process.

After her graduation Diana began her career as a rug designer at the carpet factory in Kavajë, focusing primarily on export models. She soon moved back to Tirana and was hired as an art teacher at the Mihal Grameno School and in the Visual Arts Course at the Palace of Pioneers.

During the 1980s, Diana focused on motherhood and teaching, and without a proper studio her artistic practice was somewhat neglected. However, she was periodically granted leave for creative practice, allowing her to execute several oil-on-canvas works. Most of these pieces were given away, and there is little documentation of them.

With the changes that occurred in 1990 her artistic practice blossomed with energy and productivity. There was a newly acquired freedom of expression, which had been drastically repressed in Albania after the Second World War. In the 90s, Diana returned to the pictorial approach. This emerged from an intuitive process, and she poured it solely into her textile pieces.

In 1992, Diana and Fatmir Miziri opened a joint exhibition of textiles and sculpture at the National Gallery of Arts in Tirana, with works created from the late 80s to 1992. Diana’s textile works created in the early 90s document the newfound freedom of expression, reflected in compositions that tend toward free geometrical and organic abstraction. The interplay between materials and colours, as well as breaking away from repetitive pattern weaving, set the tone for these works. Her approach, although intuitive, played a decisive role in elevating her practice, and weaving more generally, to works of art.

Regarding her technique, the works from this period were often made with poor-quality materials, frequently reused or repurposed from industrial sources predating the 1990s. During the post-communist transitional years, there were significant shortages of materials and means for producing textile works. As a result, Diana often used spare materials from the textile industry, remnants from the communist era, and combined them with leftover materials from imported products, such as coffee and rice sacks, as well as various cotton, wool, and linen threads. Some of these materials were manually dyed to achieve the desired hues. Consequently, many of her works were characterized by an approach of recycling and reuse. Most of her works were produced in her home, which was adapted to function as a studio. Family members were involved in various processes, such as spinning wool, picking apart old sacks, dyeing materials, and preparing the support structure for weaving. Every textile work was produced without the aid of machinery or a loom. Instead, Diana used auxiliary structures, like griddles, to fix the pieces she wove. Weaving was mainly done using large needles, up to 15 cm long, which she made herself with the assistance of her husband. Some of her textile works were created jointly with her husband.

In 1992 Diana was among the first Albanian fashion designers to participate in the competition broadcast on national TV on the primetime show Twelve Dances Without a Saturday. She designed and produced all the dresses, which were partly or entirely woven or embroidered. Around 1995, Diana resumed her creative practice in a small studio that she shared with her husband. In 1994 she became a member of the Linda association of women artists, and participated in many exhibitions and workshops organized by the association, which stimulated her to transform her practice further. She began exploring new techniques, producing installation works that incorporated textiles with adhesive techniques on glass and creating silhouettes on film negatives, which were projected on walls. She also experimented with intertwining textiles with metal structures, although some of these projects remained incomplete and unexhibited.

She took part in national textile exhibitions, the Onufri competition, and international exhibitions in Switzerland, Italy, France, and Germany. From 1998, she taught drawing and painting at the Jordan Misja Art Lyceum, until her death in 2005. After many years of invisibility, in 2021 Diana’s textile works were shown among the works of many other women artists from Albania, Kosovo, and the diaspora in the exhibition Ambitions at the National Gallery of Arts in Tirana and National Gallery of Kosovo, co-curated by Adela Demetja.

Text by Adela Demetja